ʻĀina Is Infrastructure

Investing in the long-term ecological and cultural productivity of Hawaiʻi.

What is Biocultural Restoration?

Hawai'i's unique landscapes and ecosystems have long been shaped by indigenous and local communities through the construction of landesque capital—long-term, infrastructure-like modifications that enhance ecological and agricultural productivity.

Forms of Landesque Capital

Landesque capital refers to permanent modifications in the agrarian landscape that have value beyond the present season or cropping cycle. These include:

- Field systems: Agricultural terraces, raised fields, traditional crop patterns

- Irrigation systems: Canals, ditches, and water management structures

- Water management: Reservoirs, dams, ponds for water storage and regulation

- Terracing: Modification of slopes into flat platforms for agriculture

- Traditional practices: Rotational farming, agroforestry, mixed cropping systems

- Cultural heritage sites: Archaeological sites, sacred places, cultural landscapes

The Problem

Despite the critical role of biocultural restoration in preserving Hawai'i's environmental and cultural heritage, current Capital Improvement Project (CIP) funding mechanisms do not explicitly recognize such projects. This mapping analysis helps identify priority investment areas where CIP funds can enhance the use value of public resources.

The Solution

Our mapping analysis identifies priority sites where CIP funds can restore these systems, enhancing food security, climate resilience, and cultural heritage simultaneously. By treating these systems as infrastructure, we can unlock long-term funding.

Historical Context

The rise and fall of landesque capital—and why collective access matters

Two Intertwined Stories

Hawaiʻi's biocultural restoration challenge has two dimensions: the physical infrastructure (loʻi, ʻauwai, fishponds, field systems) and the social infrastructure (collective land access that made communal investment possible). Both collapsed together—and both must be restored together.

The Rise and Fall of Landesque Capital

At Western contact in 1778, Hawaiian agriculture was one of the most intensive pre-industrial systems in the Pacific, supporting 400,000-800,000 people[1] Feathered Gods and Fishhooks: An Introduction to Hawaiian Archaeology and Prehistory. University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1985. through massive investments in permanent landscape infrastructure.

Peak Productivity

Hawaiian agricultural systems included:

- Irrigated Pondfield Systems (Loʻi Kalo): Complex networks of terraced taro fields with sophisticated water management.

- Dryland Field Systems: Extensive stone-bounded agricultural plots (e.g., Kona Field System spanning 21 sq miles).[2] Anahulu: The Anthropology of History in the Kingdom of Hawaii. University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Colluvial Slope Cultivation: Intensive plots on lower valley slopes.

Initial Disruption

Epidemic diseases caused population decline, but large-scale agricultural infrastructure remained largely intact as the traditional ahupuaʻa system and chiefly coordination persisted.

Critical Collapse

The most dramatic decline occurred during this period:

- Population Collapse: By 1830, population declined to ~130,000—a loss of over two-thirds.[3] Before the Horror: The Population of Hawaiʻi on the Eve of Western Contact. University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1989.

- Sandalwood Era (1812-1830): Massive labor diversion from agricultural production.

- The Māhele (1848): Land privatization broke communal investment systems.[4] Native Land and Foreign Desires: Pehea Lā E Pono Ai? Bishop Museum Press, 1992.

- Commercial Shift: Traditional taro systems gave way to potato cultivation and cattle ranching.

Final Abandonment

Most dryland field systems completely abandoned. Some irrigated systems persisted, but the era of large-scale communal investment in landesque capital had definitively ended.

Why Infrastructure Collapsed: The Loss of Collective Access

Landesque capital required communal coordination—building and maintaining ʻauwai, managing shared fisheries, coordinating seasonal harvests. When the Māhele privatized land, it didn't just redistribute property; it destroyed the social infrastructure that made collective investment possible.

Traditional System

Before 1848, land was not "owned"—it involved overlapping rights and reciprocal obligations. The ahupuaʻa integrated ecological zones from mountain to sea:

- Loʻi kalo: Valley bottom pondfields

- Kula: Upland commons for grazing, gathering

- Forests: Timber, medicine, birds

- Fisheries: Nearshore resources

Access to all zones was essential for household subsistence.

The Māhele's Impact

The Great Māhele privatized Hawaiian land with devastating results:

- Less than 1% of land (28,600 acres) awarded to commoners[5] The Hawaiian Land Hui Movement. University of Hawaiʻi Law Review, 34:568, 2012.

- Only "actually cultivated" lands counted—commons excluded

- Hawaiians "found themselves enjoined from 'trespass' on kula and in forests where they had formerly grazed animals and gathered firewood"[6] The Hui Lands of Keanae. Journal of the Polynesian Society, 92(2):175, 1983.

Loss of communal access broke the integrated resource system.

The Land Hui Response: Organized Resistance

Hawaiians didn't passively accept dispossession. Between the 1860s and 1920, they formed hui kūʻai ʻāina (land acquisition associations) to collectively purchase large tracts—often entire ahupuaʻa—and recreate communal access within Western legal structures.[7] The Hawaiian Land Hui Movement. University of Hawaiʻi Law Review, 34:557-608, 2012.

"Hawaiians knew, or quickly came to know, precisely what was happening to their world and they organized to fight against it."[12] Kahana: How the Land Was Lost. University of Hawaiʻi Press, p. 2, 2004.

Scale of Movement

- Wainiha Hui: 15,000 acres, 71 members (Kauaʻi)[8] Old Hawaiian Land Huis. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 1932.

- Mailepai Hui: 2,825 acres, 113 members (Maui)[8] Old Hawaiian Land Huis. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 1932.

- Peahi Hui: 2,000 acres, 191 members (Maui)[8] Old Hawaiian Land Huis. Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 1932.

Purpose

Hui purchased the kula lands nearest their taro patches—"perhaps the same kula lands that they had used before the Māhele." They re-established the traditional principle of common access, household use.

Wainiha Hui Constitution

The Hui Kūʻai ʻĀina o Wainiha created a hybrid governance model:

- Individual allotments: 5-acre plots for residence and gardens

- Collective management: Elected Luna Nui with konohiki-like authority

- Resource controls: Livestock limits, fishing rights, forest kapu

- Protection: Members could only sell shares to other Hawaiians

Courts Uphold Hui

Hawaiian Supreme Court recognized hui constitutions as binding agreements. Chief Justice Judd: hui rules "should be upheld and enforced by the Courts as far as possible."[9] citing Mahoe v. Puka, 4 Haw. 485, 1882.

Forced Partition

Plantation interests lobbied for partition laws. Courts reversed 30 years of precedent. The Partition Act of 1923 enabled forced breakup of hui lands for sugar and pineapple acquisition.[10] The Hawaiian Land Hui Movement. University of Hawaiʻi Law Review, 34:597-598, 2012.

Proven Principles

Where hui lands remain (like Keanae, Maui), they enable "distinctively Hawaiian community life that may exist nowhere else."[11] The Hui Lands of Keanae. Journal of the Polynesian Society, 92(2):183, 1983. Hui demonstrated that collective governance works—the model just needs modern legal protection.

Lessons for Contemporary Restoration

Land hui proved that biocultural restoration requires both physical and social infrastructure. Their successes and failures inform modern approaches:

What Worked

- Written constitutions with clear bylaws

- Elected leadership with defined powers

- Integration of individual + collective rights

- Internal dispute resolution

- Revenue generation from surplus resources

What Failed

- No corporate legal status (vulnerable to lawsuits)

- Ownership fractionalized through inheritance

- No protection against forced partition

- Reliance on judicial goodwill

Modern solutions—LLCs, community land trusts, conservation easements—can preserve hui strengths while addressing vulnerabilities. CIP funding for biocultural restoration must support collective stewardship structures, not just individual projects.

References

- 1Kirch, P.V. Feathered Gods and Fishhooks: An Introduction to Hawaiian Archaeology and Prehistory. University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1985.

- 2Kirch, P.V. Anahulu: The Anthropology of History in the Kingdom of Hawaii. University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- 3Stannard, D.E. Before the Horror: The Population of Hawaiʻi on the Eve of Western Contact. University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1989.

- 4Kameʻeleihiwa, L. Native Land and Foreign Desires: Pehea Lā E Pono Ai? Bishop Museum Press, 1992.

- 5Roversi, A. "The Hawaiian Land Hui Movement: A Post-Mahele Counter-Revolution." University of Hawaiʻi Law Review, 34:557-608, 2012.

- 6Linnekin, J. "The Hui Lands of Keanae: Hawaiian Land Tenure and the Great Mahele." Journal of the Polynesian Society, 92(2):169-188, 1983.

- 7Roversi, A. "The Hawaiian Land Hui Movement." University of Hawaiʻi Law Review, 34:557-608, 2012.

- 8Watson, L.J. "Old Hawaiian Land Huis—Their Development and Dissolution." Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 12-16, 1932.

- 9Mahoe v. Puka, 4 Haw. 485 (1882). Cited in Roversi 2012:587.

- 10Roversi, A. "The Hawaiian Land Hui Movement." University of Hawaiʻi Law Review, 34:597-598, 2012.

- 11Linnekin, J. "The Hui Lands of Keanae." Journal of the Polynesian Society, 92(2):183, 1983.

- 12Stauffer, R.H. Kahana: How the Land Was Lost. University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2004.

CIP Process

How Capital Improvement Projects (CIP) are funded in Hawaiʻi.

What funds CIP?

Capital Improvement Projects (CIP) refer to long-term infrastructure investments like buildings, roads, and utilities. In Hawaiʻi, these are primarily funded by:

- General Obligation (GO) Bonds: The main source, backed by the state's credit.

- Revenue Bonds: Repaid by specific revenue (e.g., airport fees).

- Federal Funds: Grants from federal agencies (e.g., FHWA, FEMA).

- Special Funds: Dedicated funds like the Highway Fund.

1. Project Identification

Agencies, legislators, or community stakeholders identify a capital need. Concepts are gathered into agency capital plans.

2. Executive Budget

Agencies submit CIP requests to Budget & Finance (B&F). The Governor reviews and submits the Executive CIP Budget to the Legislature.

3. Legislative Review

House and Senate committees review, amend, and add projects. The final CIP Budget and Bond Authorization bills are passed.

4. Enactment & Allotment

The Governor signs the budget, creating an appropriation. Agencies must then request specific "allotments" (release of funds) to begin spending.

The Opportunity for Biocultural Restoration

Current CIP funding is primarily directed toward conventional infrastructure. However, biocultural restoration projects—restoring traditional agricultural systems, fishponds, and native ecosystems—represent the same type of long-term, permanent improvements to public lands that CIP is designed to fund. By clarifying eligibility, we can unlock this funding for community-led stewardship.

Draft Legislation

Proposed bill to authorize bonds for biocultural restoration.

A BILL FOR AN ACT

RELATING TO CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROJECTS.

BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF HAWAII:

SECTION 1. Findings and purpose.

The legislature finds that Hawaii’s unique and fragile ecosystems are critical to the State’s economy, biodiversity, and cultural heritage. The legislature further finds that traditional land and water management systems developed and maintained through community stewardship have historically increased productive capacity, restored ecological function, and perpetuated cultural knowledge.

The legislature recognizes that such investments, sometimes described as landesque capital, include substantial, long-term improvements to public lands and waters that warrant recognition as capital improvement projects when they provide enduring public benefits.

The legislature further finds that advancing the State’s sustainability, resilience, and food security goals requires strategic investment in nature-based and culturally informed infrastructure that strengthens ecosystems while supporting community-government partnerships.

The purpose of this Act is to establish biocultural restoration as a recognized capital improvement project priority category and to guide the allocation of capital improvement project funds toward projects on public lands that advance the State’s sustainability, resilience, and food security goals.

SECTION 2. Chapter 37, Hawaii Revised Statutes, is amended by adding a new section to be appropriately designated to read as follows:

"§37-___ Biocultural restoration capital improvement projects; priority category. (a) Biocultural restoration capital improvement projects shall be recognized as an eligible and priority category for capital improvement project appropriations relating to public lands and waters.

(b) In allocating capital improvement project funds, priority consideration shall be given to biocultural restoration projects that advance one or more of the State’s sustainability, resilience, or food security goals, including but not limited to goals relating to:

- Increased local food production and food system resilience;

- Climate change adaptation, natural hazard mitigation, or ecosystem-based resilience;

- Watershed protection, water security, or soil conservation;

- Carbon sequestration or greenhouse gas emission reduction through nature-based solutions; or

- The perpetuation of Native Hawaiian or traditional ecological knowledge through active land stewardship.

(c) Eligible biocultural restoration capital improvement projects shall:

- Constitute substantial, long-term improvements to public lands or waters;

- Be proposed by a state department in partnership with a community organization;

- Demonstrate capacity to increase food production, restore traditional knowledge, or enhance ecosystem services; and

- Include a long-term stewardship and maintenance plan.

(d) Eligible project types may include:

- Loʻi kalo terraces and associated water conveyance systems;

- Loko iʻa fishponds and associated structural components;

- ʻAuwai systems;

- Traditional dryland agricultural systems; and

- Erosion control, shoreline stabilization, or watershed protection infrastructure employing culturally informed or nature-based practices.

(e) This section shall not apply to:

- Routine maintenance activities;

- Projects located on private lands; or

- Projects lacking a community partnership as described in subsection (c)."

SECTION 3. Effective date.

This Act shall take effect upon its approval.

Suitable Land

Methodology

Data sources, scoring algorithm, and suitability framework.

Suitability Analysis Approach

This analysis identifies government-owned lands suitable for traditional Hawaiian agricultural restoration. We overlay the Kurashima et al. (2019) agricultural potential model with public land ownership and current land cover to pinpoint specific restoration opportunities.

Data Sources

| Layer | Source | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Government Land Ownership | Hawaii GeoPortal | Identify public land parcels |

| Agricultural Potential | Kurashima et al. (2019) | Traditional ag suitability model |

| Hawaii Cropland Data Layer | USDA NASS HCDL V2.0 (2024) | Current land use/cover |

| Moku/Ahupuaʻa Boundaries | Hawaii Open Data | Traditional land division context |

Suitability Determination

A parcel is Suitable if it contains land meeting these criteria:

- Government owned (State, DHHL, or County)

- Kurashima model indicates agricultural potential for loʻi kalo, dryland, or agroforestry

- Not developed or water (excluded via CDL)

Each suitable parcel shows the breakdown of land cover types within its suitable area.

CDL Land Cover Categories

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| ◼ Fallow | Grassland, shrubland, barren (prime targets) |

| ◼ Forest | Forested land (requires landscape change) |

| ◼ Traditional | Taro, banana, coconut (existing use) |

| ◼ Commercial | Coffee, macadamia, etc. (existing use) |

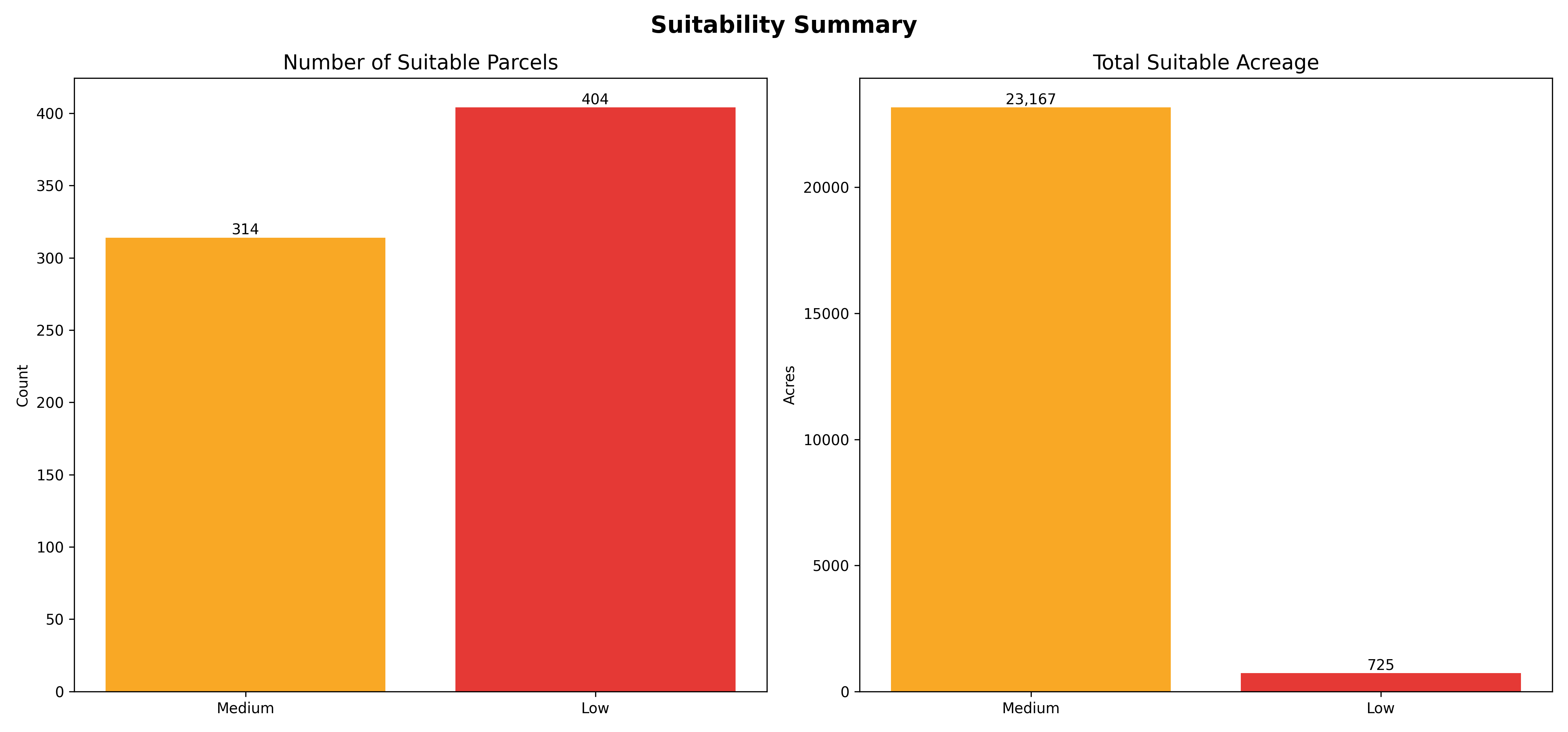

Results Summary

1,393 parcels contain suitable land totaling 44,317 acres

| Owner | Parcels | Total Suitable | Fallow | Forest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | 697 | 32,394 ac | 11,480 ac | 19,470 ac |

| State DHHL | 535 | 11,176 ac | 6,447 ac | 3,490 ac |

| Counties | 161 | 747 ac | 252 ac | 479 ac |

53% of suitable land is currently forested; 41% is fallow (prime restoration targets)

Coverage Limitation

Oʻahu parcels (~11,000 of 24,000 total) lack Kurashima raster data. While Oʻahu was included in the original study, the raster outputs were not uploaded to the ScholarSpace repository. Oʻahu parcels show as "Not Suitable" in this analysis.

References

Kurashima, N., Fortini, L. & Ticktin, T. (2019). The potential of indigenous agricultural food production under climate change in Hawaiʻi. Nature Sustainability, 2, 191-199.

USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (2025). Hawaii Cropland Data Layer V2.0.

Research Paper

Investing in Landesque Capital: Spatial Suitability for Biocultural Restoration on Public Lands in Hawai‘i

Hawai‘i’s landscape is defined by the remnants of extensive pre-industrial agricultural systems—terraces, fishponds, and field systems—that once supported hundreds of thousands of people. These systems represented massive investments in "landesque capital," or land modifications designed to yield returns over generations. However, modern state funding mechanisms, specifically Capital Improvement Project (CIP) bonds, largely restrict "infrastructure" investment to gray infrastructure (roads, sewers), leaving biocultural restoration to rely on precarious short-term grants. This paper argues that landesque capital functions as essential public infrastructure. Consequently, biocultural restoration—the revitalization of these social-ecological systems—should be viewed not merely as cultural preservation, but as both the means and the outcome of a resilient state infrastructure strategy, demonstrated by the allocation of long-term capital funding (CIP). We find extensive overlap between public lands and high-potential traditional agricultural zones, identifying 313,882 acres of suitable land. Our analysis reveals that 14% of these lands are currently fallow, representing an immediate, low-conflict opportunity for pilot projects, while the majority (61%) are forested and require long-term capital investment for restoration. We propose that the State of Hawai‘i can enhance climate resilience and food security by recognizing landesque capital as public infrastructure. Finally, leaving the question of specific tenure mechanisms open, we suggest that future research into how tenure, collective access, and community governance function in managing these public lands could inform social-organizational approaches to "land back" efforts.

1. Introduction

Across the Hawaiian archipelago, the physical traces of a highly productive past remain visible in the landscape. Stone walls of dryland field systems stretch across leeward slopes, terrace complexes (lo‘i) step down windward valleys, and the walls of fishponds (loko i‘a) encircle coastal bays. These features are not merely archaeological sites; they are the remnants of what economists Sen (1959) and Brookfield (1984) term "landesque capital"—permanent modifications to the land that provide returns over long periods. In pre-contact Hawai‘i, these systems functioned as the primary infrastructure of society, underpinning a population estimated between 400,000 and 800,000 (Kirch 2007).

Today, however, the mechanisms for funding public infrastructure in Hawai‘i have become decoupled from these landscape-based systems. The State of Hawai‘i’s Capital Improvement Project (CIP) budget—funded primarily through General Obligation bonds—allocates billions of dollars annually for "gray" infrastructure such as highways, harbors, and public buildings. In contrast, the restoration of traditional agricultural systems, which provide comparable public benefits in terms of flood mitigation, aquifer recharge, and food security, is largely excluded from this capital funding stream. Instead, biocultural restoration projects are forced to rely on piecemeal, short-term funding sources like Grants-in-Aid (GIA), which prohibit the long-term planning and "heavy lifting" (e.g., wall restoration, dredging) required to revitalize these systems.

This paper addresses this policy gap by reframing biocultural restoration as a form of capital infrastructure investment. We argue that restoring a fishpond wall or an irrigation network on public land is functionally equivalent to repairing a state reservoir or sea wall and should be eligible for the same long-term financing mechanisms.

To operationalize this concept, we conduct a spatial suitability analysis of state-owned lands to identify areas where biocultural restoration is most ecologically and socially viable. By intersecting government land ownership records with data on indigenous agricultural potential (Kurashima et al. 2019) and State Land Use Districts, we identify a "restoration-ready" land base. Furthermore, we examine the historical context of the "Land Hui" movement as a precedent for community-based management of these resources, suggesting that a return to neo-traditional tenure arrangements—where the state holds title but communities hold long-term stewardship rights—offers a viable pathway for revitalizing Hawai‘i’s landesque capital.

2. Context: A History of Investment, Decline, and Resilience

2.1 The Rise of Landesque Capital

Prior to Western contact, Hawaiian society was characterized by intensive investment in agricultural infrastructure, which Allen (1991) describes as the "material engine" of the Hawaiian archaic state. This was not subsistence farming in a simple sense, but a system of "public works" maintained by communal labor under chiefly direction.

The development of this infrastructure followed distinct geological pathways (Kirch 1994). On the older, eroded islands of Kaua‘i and O‘ahu, investment focused on lo‘i kalo (irrigated taro terraces), which utilized sophisticated hydraulic engineering to divert stream water into valley-wide complexes. These systems were highly effective: Palmer et al. (2009) found that irrigation water in these systems supplied nutrients (calcium) at rates 100 times higher than natural soil weathering, demonstrating their function as high-performance nutrient delivery infrastructure.

On the younger islands of Maui and Hawai‘i, investment shifted to "farming the rock" through vast dryland field systems (such as the Kohala and Kona field systems), where field walls and mulching strategies modified microclimates to support sweet potato and ulu production (Kirch & Sahlins 1992; Vitousek et al. 2004). These investments were capital-intensive: they required immense upfront labor to construct but yielded increasing returns over generations, effectively "banking" labor in the landscape.

2.2 The Collapse (1820–1880)

The disintegration of these systems was neither accidental nor purely environmental. It was a structural collapse driven by converging factors between 1820 and 1880:

- Political Shock (1819): The abolition of the kapu system (ʻAi Noa) removed the religious authority of the konohiki (land managers) to command the communal labor necessary for cleaning ditches and repairing walls, destabilizing the maintenance regimes required for large-scale infrastructure (Earle 1978).

- Demographic Collapse: Introduced diseases reduced the native population by over 70%, decimating the labor force required to maintain labor-intensive infrastructure (Kirch 2007).

- The Sandalwood Trade: The rapid integration into the global economy shifted labor from maintaining "landesque capital" (food production) to extracting natural capital (sandalwood) for immediate trade, leading to the first historical famines (Rice 2020).

- The Māhele (1848): The transition to fee-simple property fragmented the ahupua‘a system. The traditional right of access to kula (uplands) and kai (sea) was severed from the kuleana (house/farm) plots awarded to commoners, rendering the integrated resource system dysfunctional for many families (Roversi 2012).

By 1880, the era of large-scale communal investment in agricultural infrastructure had effectively ended, replaced by plantation agriculture. Yet, the durability of the initial investment remained visible: rice farmers in the late 19th century utilized the "shell" of abandoned lo‘i as "successional capital," repurposing the terraces for global export crops (Bayliss-Smith et al. 1997). However, the rise of industrial sugar ultimately decommissioned much of this system through "dewatering"—constructing massive ditches that diverted water away from traditional watersheds, physically destroying the functional capacity of the lo‘i (MacLennan 2014).

2.3 The Response: The Land Hui Movement

In the wake of the Māhele, Native Hawaiians did not passively accept dispossession. They innovated new legal structures to maintain communal land tenure within the framework of Western property law. Between the 1860s and 1920s, groups of Hawaiians formed "Land Huis"—cooperative associations that pooled resources to purchase entire ahupua‘a (Roversi 2012; Watson 1932).

The Hui system functioned as an early form of biocultural restoration and resilience. A Hui would hold the land in common, often adopting a constitution and bylaws that mirrored traditional resource management: electing a luna (manager) to oversee water rights, enforce grazing limits, and maintain shared infrastructure, while allocating individual plots for family use. This hybrid governance structure allowed communities to retain access to the full vertical resource zone (mountain to sea) despite the legal fragmentation of the surrounding landscape.

Although many Huis were eventually dissolved by partition suits or hostile acquisition, they established a crucial precedent: that communal management of land, coupled with formal legal tenure, is a viable mechanism for stewardship.

2.4 Modern Landesque Capital Investment and the Funding Gap

Today, a new wave of "Land Huis" has emerged in the form of non-profit community organizations seeking to restore these same landscapes. Groups like Paepae o Heʻeia (O‘ahu), Hui Mālama o Ke Kai (Maui), and Waipā Foundation (Kaua‘i) are actively restoring fishponds and lo‘i systems.

However, these modern organizations face a critical barrier that their 19th-century predecessors did not: they operate primarily on public lands (state or county) without the benefit of ownership capital. While the State of Hawai‘i acts as the legal landowner (often via the Department of Land and Natural Resources), it rarely invests capital funds into the restoration of the "assets" on these lands. Instead, community groups are left to patch together short-term grants for what is essentially public infrastructure maintenance.

For example, the restoration of the 7,000-foot kuapā (wall) at Heʻeia Fishpond involves moving tons of coral and basalt—a capital project in every engineering sense (Paepae o Heʻeia 2025). Yet, because it is classified as "cultural practice" rather than "infrastructure improvement," it largely falls outside the scope of the State’s primary capital financing mechanism, the General Obligation bond market.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study Area and Data Sources

This analysis covers the major Hawaiian Islands (Hawai‘i, Maui, O‘ahu, Kaua‘i, Moloka‘i, Lāna‘i). The spatial framework operates on the NAD83(HARN) / UTM zone 4N projected coordinate system (EPSG:3750) to ensure accurate area calculations.

We integrated four primary datasets to identify suitable sites:

- Government Land Ownership: Detailed parcel data from the Hawaii Statewide GIS Program, filtered to exclude federal lands and retain only State and County owned parcels. This defines the "public land" universe where state CIP funding is applicable.

- State Land Use Districts (SLUD): Official district boundaries (Agriculture, Rural, Conservation, Urban) which define the regulatory envelope for each parcel.

- Indigenous Agricultural Potential: The spatial model developed by Kurashima et al. (2019), which maps the pre-contact extent of intensive agriculture.

- Current Land Cover: The Hawaii Cropland Data Layer (HCDL) v2.0 (Li et al. 2024), a 10-meter resolution raster product developed through a collaboration between USDA NASS and the University of Hawaii at Manoa. This dataset leverages AlphaEarth Foundations geospatial embeddings to provide crop-specific classification, which we used to identify existing development or conflicts.

3.2 Indigenous Agricultural Modeling

To ground our analysis in traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and biophysical reality, we utilized the Kurashima et al. (2019) geospatial model. This model reconstructs the "fundamental niche" for traditional Hawaiian agriculture based on three primary systems:

- Lo‘i Kalo (Wetland Taro): Modeled based on the presence of perennial streams, hydraulic soil types, low slope (< 10°), and elevation (< 415m).

- Dryland Field Systems: Modeled for areas with 750–1600mm annual rainfall, slope < 12°, and substrates of sufficient geological age (> 400kyr) to support soil fertility.

- Agroforestry: Defined by broader parameters (slope < 30°, rainfall > 750mm) representing the "colluvial slope" systems that often buffered the core agricultural zones.

Our analysis specifically targets the "High Potential" zones from this model, representing the optimal convergence of climatic and geomorphic conditions.

3.3 Suitability Analysis & Scoring

To identify "restoration-ready" public lands, we performed a spatial intersection of these layers using Python (Geopandas, Rasterstats). We utilized the NAD83(HARN) / UTM zone 4N projected coordinate system (EPSG:3750) for all geometric calculations to minimize distortion.

We developed a composite Suitability Score (0–100) to rank sites based on their viability for ahupua‘a-scale restoration. The scoring algorithm weights three factors:

- Indigenous Agricultural Potential (40%): Derived from the Kurashima model rank.

- High = 100 points

- Medium = 60 points

- Low = 30 points

- Land Use Compatibility (35%): Based on the regulatory ease of restoration.

- Agricultural District = 100 points

- Rural District = 75 points

- Conservation District = 50 points (Restoration possible but regulatively burdensome).

- Urban District = 25 points.

- Parcel Size (25%): Favoring larger contiguous parcels that allow for system-scale restoration.

- > 100 acres = 100 points

- 25–100 acres = 75 points

- 5–25 acres = 50 points

- < 5 acres = Scaled linearly down to 0.

Exclusion Criteria: We utilized the HCDL v2.0 to filter for conflict. Using zonal statistics (rasterstats), we assigned each parcel a dominant land cover class. Parcels where the majority pixels were classified as "Commercial/Industrial" or "High Intensity Developed" were flagged for exclusion, ensuring that priority sites are not currently occupied by critical modern infrastructure.

3.4 Contextual Validation

To validate the model, we calculated a Proximity Score based on the distance to known, successful biocultural restoration projects (Reference Projects) such as Paepae o Heʻeia or Waipā Foundation. We employed an inverse linear distance function with a 5km maximum buffer:

- 0 meters (adjacent) = 100 points

- 5,000 meters = 0 points

This score serves as a proxy for social readiness and the potential for knowledge transfer, assuming that proximity to existing practice lowers barriers to entry for new projects.

4. Results

4.1 Distribution of Suitable Lands

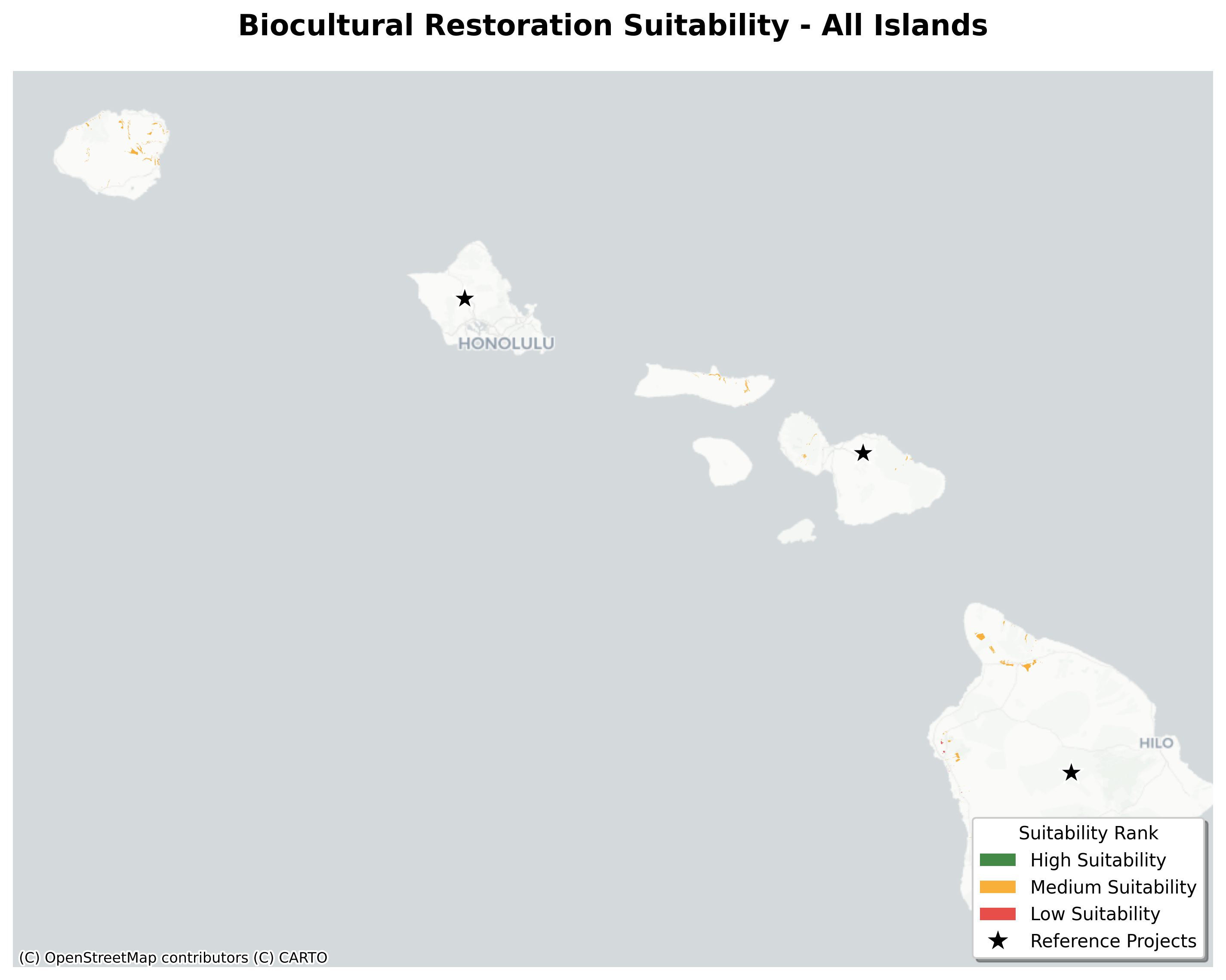

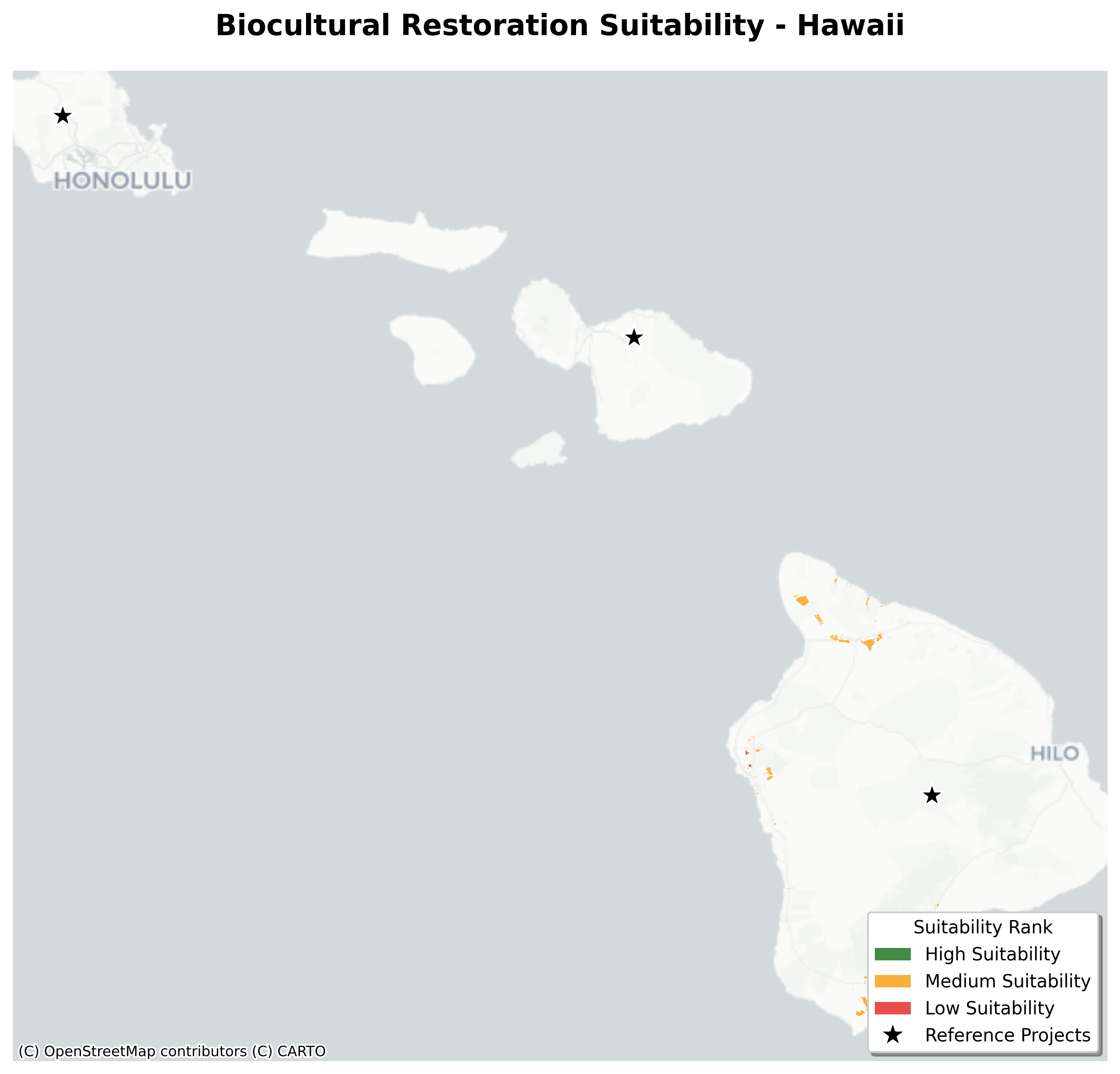

The spatial analysis evaluated government-owned parcels across the main Hawaiian Islands (Figure 1). Of these, 1,639 parcels (approximately 313,882 acres) were identified as "Medium Suitability" or higher (Score ≥ 40), representing the core land base for potential biocultural restoration.

Geographic Distribution:

Hawai‘i Island dominates the portfolio in terms of count, while Kaua‘i holds significant large-acreage opportunities. Note: O‘ahu was excluded from this final suitability calculation due to data gaps in the underlying Kurashima et al. (2019) public dataset release; however, high-potential areas are known to exist there and will be added as data becomes available.

| Island | Parcel Count | Total Acres | Mean Suitability Score | Primary Opportunity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hawai‘i | 1,327 | 151,097 | 64.26 | Dryland & Lo‘i |

| Kaua‘i | 165 | 104,979 | 49.42 | Agroforestry |

| Maui | 76 | 35,133 | 46.13 | Agroforestry |

| Moloka‘i | 68 | 22,540 | 61.50 | Agroforestry |

| Lāna‘i | 3 | 133 | 50.27 | Agroforestry |

System Type Analysis:

Breaking down the suitable acreage by traditional agricultural system reveals that Dryland Field Systems represent the largest restoration opportunity by area, particularly on Hawai‘i Island. Agroforestry potential is the dominant system on Kaua‘i, Maui, and Moloka‘i. Lo‘i Kalo potential, while smaller in absolute acreage (approx. 556 acres identified in the core analysis set), represents a high-value cultural asset concentrated on specific hydrological features.

Land Use District Analysis:

The intersection with State Land Use Districts (SLUD) reveals a distinct bifurcation in restoration opportunities:

- Agricultural District: Contains 9,793 government parcels (1.54 million acres) with the highest mean suitability score (43.98). These lands represent the "low-hanging fruit" for restoration—areas where both the ecological potential and the regulatory framework align.

- Conservation District: Contains 2,845 parcels but a massive land area (1.44 million acres). While the mean suitability score is lower (30.32), this is largely due to the scoring penalty applied to the Conservation district. Critically, many of Hawai‘i’s most intact historical systems (e.g., upper valley lo‘i and forest zones) are located here.

4.2 Ownership Patterns

The State of Hawai‘i (DLNR and other agencies) is the primary landowner of suitable sites, holding over 265,000 acres of the high-suitability land base.

- Department of Hawaiian Home Lands (DHHL): DHHL holds the highest number of suitable parcels (961), comprising 33,617 acres. This high parcel count implies a fragmented land base that may benefit from the "Hui" model of aggregated management.

- State (Other/DLNR): Holds the largest contiguous acreage (265,518 acres), including massive forest reserves on Hawai‘i and Kaua‘i suitable for agroforestry.

- County Lands: County governments collectively own 164 suitable parcels (6,059 acres), often in closer proximity to population centers.

Top Suitability Sites:

The analysis identified several "perfect" candidates (Score = 100), including an 8,353-acre State parcel on Hawai‘i Island. These sites represent immediate opportunities for pilot "Landesque Capital" investment projects.

5. Discussion

5.1 Reframing Infrastructure: The "Restoration-Ready" Land Base

The results demonstrate that the State of Hawai‘i possesses a vast inventory of "restoration-ready" land—over 1.5 million acres where public ownership overlaps with indigenous agricultural potential. Currently, these lands are viewed primarily as conservation assets (passive management) or agricultural leases (commercial management).

We propose a Tiered Restoration Strategy based on current land cover, which dictates the level of capital investment required:

- Tier 1: Immediate Opportunity (Fallow/Shrubland): Approximately 14% of the suitable land base (approx. 3,300 acres in the core set) is currently classified as fallow. These lands have minimal conflicting uses and require the lowest barrier to entry—primarily invasive species removal and infrastructure repair. These are prime candidates for immediate "pilot" CIP projects.

- Tier 2: Negotiated Restoration (Pasture): A significant portion (**24%**) is currently used for grazing. Restoring these lands requires a "negotiated" approach, potentially integrating silvopasture models where native trees and dryland crops coexist with managed grazing, rather than displacing current lessees.

- Tier 3: Heavy Lifting (Forest): The majority (**61%**) is currently forested, often with invasive species. Restoring these systems represents a massive capital undertaking—clearing, terracing, and replanting—that fits the definition of "heavy infrastructure" work suited for long-term bond financing.

By reframing these landscapes as public infrastructure, the State could justify the use of CIP bonds to restore them. For example, the Tier 1 parcels represent sites where capital investment in wall repair and irrigation reconstruction would yield direct returns in aquifer recharge and flood mitigation—services that otherwise require expensive gray infrastructure.

5.2 The Conservation Paradox

A critical finding is the vast acreage of high-potential land locked within the Conservation District (1.44 million acres). While intended to protect resources, the strict regulations of the Conservation District often hinder the restoration of the very biocultural systems that created those resources.

Restoring a lo‘i in a Conservation District requires a Conservation District Use Permit (CDUP), a costly and bureaucratic process that treats traditional stewardship akin to development. Our analysis suggests that a significant portion of the state's "landesque capital" remains dormant not because of ecological unsuitability, but because the regulatory framework focuses on preservation (static) rather than restoration (active).

5.3 Future Research: Tenure and Governance

While this analysis identifies where restoration should happen, it leaves open the question of how tenure should be structured. The "Land Hui" history suggests that long-term community stewardship is essential for maintaining these systems.

Future research should explore:

- Neo-Traditional Tenure: How can modern legal instruments (e.g., long-term stewardship leases, community-based subsistence fishing areas) replicate the functional benefits of the Hui system on public lands?

- Land Back Mechanisms: How can the identification of these "restoration-ready" public lands inform the social-organizational approaches of #LandBack efforts? Specifically, how can community governance structures be designed to manage these large-scale infrastructure assets effectively?

6. Conclusion

Biocultural restoration is not merely a cultural project; it is a capital improvement strategy for a changing climate. Our analysis confirms that the State of Hawai‘i holds the keys to a vast system of dormant landesque capital—infrastructure that, if restored, could provide food security and climate resilience for generations.

By recognizing these ancient systems as public infrastructure and aligning capital funding (CIP) with their restoration, Hawai‘i can move beyond a model of passive conservation to one of active, abundance-generating stewardship. The land is ready; the policy just needs to catch up.

Data Availability Statement

The code used for the spatial analysis, including scoring algorithms and data processing scripts, is available in the GitHub repository at https://github.com/ainacip/ainacip. The processed datasets, including the "Ideal Sites" shapefiles and prioritization results, are archived within the repository's data/processed/ directory. Raw data sources (State GIS, HCDL) are publicly available from their respective agencies.

7. References

Key Academic Sources

- Allen, J. (1991). The role of agriculture in the evolution of the pre-contact Hawaiian state. Asian Perspectives, 30(1), 117-132.

- Bayliss-Smith, T., Burt, B., & Clerk, C. (1997). From taro garden to golf course? Alternative futures for agricultural capital in the Pacific Islands. In The Evolving Culture of South Pacific Agriculture.

- Brookfield, H.C. (1984). Intensification Revisited. Pacific Viewpoint.

- Earle, T. (1978). Economic and social organization of a complex chiefdom: The Halelea district, Kaua'i, Hawaii. University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology.

- Kirch, P.V. (1994). The wet and the dry: Irrigation and agricultural intensification in Polynesia. University of Chicago Press.

- Kirch, P.V. (2007). Hawaii as a Model System for Human Ecodynamics. American Anthropologist, 109(1), 8-26.

- Kirch, P.V. & Sahlins, M. (1992). Anahulu: The Anthropology of History in the Kingdom of Hawaii. University of Chicago Press.

- Kurashima, N., et al. (2019). The potential of indigenous agricultural food production under climate change in Hawaiʻi. Nature Sustainability, 2, 88–98.

- Lincoln, N.K., et al. (2018). Restoration of ‘Āina Malo‘o on Hawai‘i Island: Expanding Biocultural Relationships. Sustainability, 10(11), 3985.

- MacLennan, C. A. (2014). Sovereign Sugar: Industry and Environment in Hawaiʻi. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- Palmer, M. A., et al. (2009). Sources of nutrients to windward agricultural systems in pre‐contact Hawai'i. Ecological Applications, 19(6), 1444-1453.

- Rice, S. (2020). Famine in the Remaking: Food System Change and Mass Starvation in Hawaii. West Virginia University Press.

- Roversi, A. (2012). The Hawaiian Land Hui Movement: A Post-Mahele Counter-Revolution in Land Tenure and Community Resource Management. University of Hawai'i Law Review, 34, 557-608.

- Sen, A.K. (1959). Choice of Techniques.

- Vitousek, P. M., et al. (2004). Soils, agriculture, and society in precontact Hawaii. Science, 304(5677), 1665-1669.

- Watson, L.J. (1932). Old Hawaiian Land Huis - Their Development and Dissolution. Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

Community & Policy Resources

- Brown, C.F., et al. (2025). AlphaEarth Foundations: An embedding field model for accurate and efficient global mapping from sparse label data. arXiv preprint.

- Li, Z., et al. (2024). Innovative Crop Mapping in Hawaii: The First 10-Meter Resolution Cropland Data Layers for 2023. 12th International Conference on Agro-Geoinformatics.

- Paepae o Heʻeia. (2025). Restoration of Heʻeia Fishpond. Community Report.

- State of Hawai'i. (2022). Act 279: Relating to the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands. Session Laws of Hawai'i.

- State of Hawai'i. (2020). Testimony regarding SB3019: Relating to Conservation Districts.